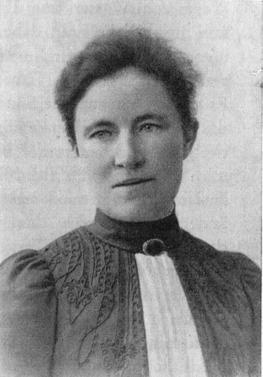

Marcell O'Grady Boveri in 1897

The Marcella O’Grady Boveri Student Cancer Research Medal honors the pioneering research and foundational leadership in women’s scientific advancement achieved by MIT’s first female graduate in biology. Boveri was widely known to hold herself and her students to high standards in terms of critical thinking, industry, and accuracy in observation and expression. This award recognizes young researchers who exemplify and uphold this legacy.

The Boveri Medal is awarded annually to a rising MIT senior in any department who has conducted significant cancer research in a Koch Institute laboratory as an undergraduate. In addition to the medal, the recipient will also receive a financial prize and have an opportunity to present an overview of their research in a Koch Institute community forum.

Nominations for the inaugural Boveri Medal are due by noon on Wednesday, May 22, 2024. Please see the "Eligibility and Timeline" section below for more details.

Who is eligible: Nominations are open to intra- and extramural Koch Institute laboratories. The nominee must be a rising senior, of any gender or major, who has carried out substantial cancer or cancer-relevant research in the nominating laboratory (for example, significant contributions to experimental design, execution, and analysis and/or co-authorship of a paper) and will continue their work into the following academic year.

Who can nominate: Each Koch Institute faculty member may nominate up to two undergraduate trainees.

How to nominate: PIs must submit nominations to ki-fellowships@mit.edu by noon on Wednesday, May 22, 2024. Please use the subject line: Boveri Medal Nomination. Please combine all materials into one PDF.

The nomination package should include the following:

- The name, laboratory, and project title of the nominee.

- A summary, 500 words maximum, describing the work conducted by the nominee, in the context of the larger cancer research project.

- A letter of recommendation from the PI, two pages maximum, which may include quotes or statements from the nominee’s lab mentor. Boveri was widely known to hold herself and her students to high standards in terms of critical thinking, industry, and accuracy in observation and expression. Tell us how the nominee exemplifies and upholds this legacy.

Timeline: The recipient and their PI will be notified of the award in June. Formal award and announcement of the prize, as well as the winner’s presentation, will take place during the fall semester following selection.

A Boston native, Marcella O’Grady Boveri attended the public Boston Girls’ High School. In 1885, she became the first woman graduate in biology from MIT. (Though Course 7 at the time was called Natural History and would not become Biology until 1889, O’Grady’s coursework and research was singularly focused on biology and the life sciences.) After leaving MIT, she taught science at the Bryn Mawr School, a girls preparatory school in Baltimore.

Two years later, O’Grady was awarded the Fellowship in Biology for 1887-1889 for advanced study at Bryn Mawr College. Then a rare for a woman to be accepted for graduate study, it was even more exceptional for her to be given the opportunity to pursue a doctorate. O’Grady undertook studies in comparative zoology and embryology, while also serving as a teaching assistant to E.B. Wilson. Her Ph.D. program included extensive laboratory work, which she conducted at the Marine Biology Laboratory at Woods Hole in Massachusetts. O’Grady’s work sufficiently impressed Bryn Mawr’s trustees that she was named “Fellow by Courtesy” and her appointment renewed for the 1889-1890 academic year. However, she postponed her research and degree to accept an unmissable opportunity: a teaching position at Vassar College in New York.

Following an administrative reorganization of the natural sciences at Vassar, O’Grady found herself promoted within a year to assistant professor, then to sole member and head of the newly formed Department of Biology. Embracing this new mantle and with full discretion over curriculum design, she emphasized the importance of students engaging the scientific method and conducting their own original research. During her tenure enrollment increased, the curriculum expanded rapidly to seven courses and the faculty grew to four members.

In 1896 O’Grady took a research sabbatical and, on the recommendation of E.B. Wilson, went to Würzburg University (where she was also the first woman admitted to study science) to work with cytologist Theodor Boveri, director of its Zoological-Zootomical Institute. A year later she and Boveri were married and, until his passing in 1915, she was her husband’s close scientific collaborator. Although she published her research in a dissertation titled, “On Mitoses in Unilateral Chromosome Binding,” she never defended it thus was not formally awarded a doctorate.

During a visit back to the United States in 1926, Boveri was recruited to establish and run the science program at the newly opened Albertus Magnus College in New Haven, where she remained for 16 years. In her early years there, she penned an English translation of The Origin of Malignant Tumors, a monograph advancing the chromosome theory of cancer that she had co-written with her husband; published in 1929 it is the written work for which she is best known. The Boveris’ theory was based on the view that cancer is a cellular problem, which begins from a single cell with a chromosomal abnormality that is passed on to all its descendants and causes rapid cell proliferation.

Boveri was an accomplished researcher and educator whose work has helped shape modern cancer research and science education. Her insistence, at each of the programs she led, that undergraduates conduct primary research helped to establish the practice as part of standard science curricula. Boveri’s work to bolster and expand science instruction, including research opportunities, at leading women’s educational institutions helped to nurture and train the first critical mass of formally trained and credentialed women scientists. And ultimately, it was in marine organisms like those that Boveri had studied so eagerly at Woods Hole, that she and her husband made discoveries about the cellular origins of cancer that have informed, and continue to guide, cancer research programs at her alma mater and beyond.